Assessing Research about the Gwangju People’s Uprising

Full Text

The role of the May 18 Institute in the international comprehension of the events of 1980 is not simply confined to the academic arena, although that is the primary place where the Institute has had an impact. Through its annual international conferences, the Institute has brought researchers from more than 18 countries to Korea, where they have learned not only facts about the uprising but have had a chance to visit Mangwoldong cemetery, to experience Gwangju’s vibrant civil society and to meet participants in the uprising.

In my remarks today, I will begin by mentioning some of the more prominent English language accounts of Korean history and comment upon the place that they ascribe to the Gwangju Uprising. By English-language accounts, I mean books originally published in English. Some Korean language books have been translated, most notably Lee Jae-eui’s history of the uprising. But my focus is to try to help us understand the depth with which 518 has been understood as central to Korean history by foreigners.

Despite Korea’s rich history of uprisings, they are seldom adequately addressed in Korean studies. In one of the most popular English-language histories, Korea’s Place in the Sun, Professor Bruce Cumings, the foremost American Koreanist, devotes only one page to the Gwangju Uprising of more than 500 pages in his book. He has only one paragraph on the June 1987 uprising. Thus, the two key events that overwhelmed the military dictatorship and won democracy are practically ignored. Moreover, Cumings mistakenly tells us the 1987 uprising lasted 10 days, from June 10 to 20, when, in fact, people sustained it for nineteen days—from June 10 to 29—and would have continued longer if the dictatorship had not capitulated to their insistence upon direct presidential elections.1 Cumings also places the Buma Uprising in August and September 1979, when it occurred from October 16 to 18. He informs readers that Chun Doo-hwan was forced from office in June 1987 (while he actually finished serving the remainder of his term until January 1988).2 Inattention to detail may be excused, but Cumings’ work reflects a broader sense in which uprisings are not understood as a major variable in the constellation of forces that shaped modern Korea. As I discuss below, a Eurocentric view of civil society contributes to this problem.

Martin Hart-Landsberg’s insightful book, The Rush to Development, offers only a few paragraphs on Gwangju and two sentences on the June Uprising. Sadly, in Koo’s important book, Gwangju 518 is mentioned only once, and while on that topic, he twice mentions the 517 military coup as having enormous influence on Korean history but does not comprehend the significance of 518.3 Hagen Koo claims most people arrested during the June Uprising were workers, an inaccurate statement. Linda Lewis’s impressive work treats Gwangju’s movement as victims of violence rather than subjects of history.4

Given the marginalization of 518 in mainstream American histories, I believe the main tasks ahead for the May 18 research are threefold:

To transcribe and translate recordings (both audio-video and simply audio) of the seven rallies in liberated Gwangju from May 22 to May 26

Theoretically to challenge the Eurocentric assertion of what constitutes "civil society" because of its role in ascribing to the United States a predominant role in Korean democratization while minimizing the role of the Korean minjung

Empirically to challenge and refute the myths currently circulating of North Korean influence on the uprising

Section Notes:

1 Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: Norton and Co., 1997), 387

2 Bruce Cumings, “Civil Society in West and East,” in Korean Society: Civil Society, Democracy, and the State, ed. Charles Armstrong (London: Routledge, 2007)

3 Hagen Koo, Korean Workers: The Culture and Politics of Class Formation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 120.

4 Linda Lewis, Laying Claim to the Memory of May: A Look Back at the 1980 Kwangju Uprising (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002); Juna Byun and Linda Lewis (editors), The 1980 Gwangju Uprising After 20 years: The Unhealed Wounds of the Victims (Seoul: Dahae Publishers, 2000).

1. To transcribe and translate recordings (both audio-video and simply audio) of the seven rallies in liberated Gwangju from May 22 to May 26

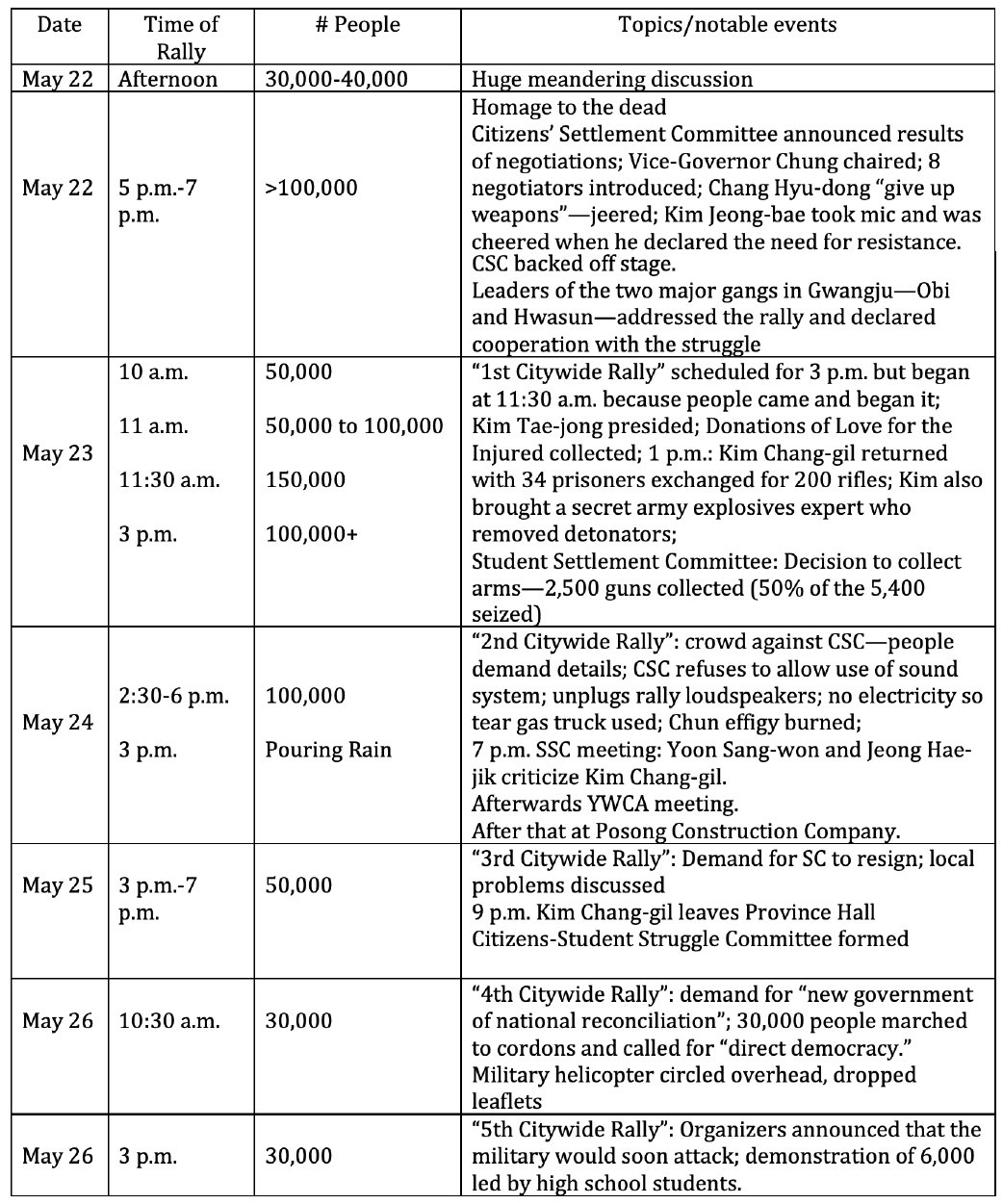

At the heart of the meaning of the 518 uprising were the love and solidarity of citizens for each other. The seven rallies that occurred in liberated Gwangju from May 22 to May 26 may provide textual data for these emotions. Using careful CA (conversation analysis) to minutely study the discursive patterns of the rallies could be a fruitful avenue of inquiry. As far as I know, little comprehensive work has been done to outline the essential characteristics of these events: the number of participants, the times of the rallies, the points discussed, and the outcomes of the discussions. In Asia’s Unknown Uprisings, I attempted to develop a typology of these rallies, which I reproduce below.

Table 1: Rallies in Liberated Gwangju

I hope the above table serves as a starting point for others who can painstakingly constructs of very detailed outline of the rallies.

In my view, the rallies corresponded to the ideal speech community discussed by German philosopher Jü rgen Habermas.5 In this discourse, everyone was equal, and all could enter public space; disagreement and debate were uncensored, the debate was political and highly moral, and the context was rooted in the vital to needs of the lives of citizens. The space in liberated Gwangju was as close as reality has come to Habermas’s ideal-typical public sphere. One of the most meaningful tasks ahead for the May 18 could be to transcribe tapes that were made of the daily rallies and also to translate them into English so that foreign researchers can attempt to do conversation analysis of these rallies. Some Korean analysts (including distinguished scholar Choi Jungwoon) insist the rallies were not forms of direct democracy but rather simply public arenas for exhortation and encouragement, not arenas in which controversies could be openly discussed and resolved. This is a question that needs to be studied through CA.

Section Notes:

5 See his book, Communication and the Evolution of Society (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984).

2. Theoretically to challenge the Eurocentric assertion of what constitutes "civil society" because of its role in ascribing to the United States a predominant role in Korean democratization while minimizing the role of the Korean minjung

518 was a gift of Korea’s deeply rooted civil society. The economic marginalization of the Honam region through the military dictatorship’s industrialization along the Seoul to Busan corridor had a positive effect in so far as Honam’s traditional cultural bonds remained intact. In other parts of Korea the extended family was shattered, regional dialects disappeared, and group solidarity quickly turned into the struggle for individual enrichment.

In my view, two great myths about Korean democratization have been widely propagated. Both accounts diminish or even dismiss the importance of South Korean civil society. The first is the nonsensical allegation of North Korean involvement in 518. This is a pernicious and false allegation to which I will return below. More insidious and destructive, however, is the myth of the Carnegie Council and others that it was the United States and Roh Tae-woo who brought democratization to Korea in 1987. Roh and Gaston Sigur are hailed as a champion of democracy while the minjung of Koreans, who risked life and limb during 19 consecutive days of illegal protests, disappear from history.

Let’s set the record straight. At the beginning of 1987, the U.S. government believed Chun was going to serve out his term in 1988 and expected him to appoint a suitable successor. A secret 1984 Blue House report, “Study of the Peaceful Turnover of Political Power,” considered a four-phase plan to permit elections only in the year 2000. When U.S. Secretary of State George Schultz visited Seoul in early 1986 and again in 1987, he supported a delay in the transition. Clearly, at the beginning of 1987, U.S. policymakers thought their Korean assistants would be able to manage to stay in power for many years to come. Massive protests would soon cause the American position to change, but the history they wrote emphasized their own role in bringing democracy to Korea.

During the June Uprising, early street victories won by protesters clearly alarmed Chun. He ordered the Army, Air Force, and Navy to be ready to mobilize, and reviewed plans to implement martial law. On June 10, the ruling party had labeled the demonstrations “overt violations of basic order” and publicly hinted at the possibility of martial law. U.S. Ambassador Lilley attended the ruling party’s convention where Roh was nominated—a clear public signal of U.S. support for Chun’s orchestration of Roh’s succession. On June 15, Roh Tae-woo—as the dictatorship’s official candidate to succeed Chun—told the central executive committee of the ruling party “violent demonstrations that may shake the national principle from its roots cannot be tolerated.”

Top U.S. officials worried. On June 18, US president Reagan sent Chun a letter cautioning him not to use the military. He urged a resumption of negotiations with opposition parties. The next day at 4:30 in the afternoon, only a few hours before ROK troops were scheduled to deploy, Chun suspended the mobilization plan.6 Interviewed in his home by a sympathetic analyst in 1998, Chun maintained that U.S. pressure, evident in Reagan’s letter and in a personal meeting he had with U.S. Ambassador Lilley on June 19, was the key reason for his cancellation of his order to deploy army units to urban areas. In his meeting with Chun, Lilley warned that martial law might provoke another Gwangju Uprising. To emphasize U.S. concerns, Reagan dispatched Gaston Sigur as a special envoy for the second time on June 22. The following day, Sigur reiterated to Chun in no uncertain terms that the United States would not support a military crackdown as they had in 1980.

Looking back at the June Uprising and Korea’s turn to democracy, the prestigious Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs concluded that Roh Tae-woo was the key figure in the transition from dictatorship to democracy. Following a long line of thinking that Great Men of history are its motor force, the transition was analyzed in terms of personalities. The widespread misconception among U.S. elite policymakers that Korea’s democratic transition was “elite-led” serves to justify the Chun dictatorship as benign, superior to Chinese Communist autocrats,7 and deemed Roh Tae-woo a participant in the democratization movement—rather than his actual position as its enemy.

Eurocentric views of civil society help to explain these mistaken understandings. The Carnegie report explicitly stated that Korean “civil society was weak,” and the Gwangju Uprising and June protests of only marginal significance. The Carnegie Council believed Korean civil society was weak, but empirical history (from the April 19 overthrow of Rhee to the Gwangju and June Uprisings) reveals the critical role of civil society in overthrowing U.S.-imposed military dictatorships.

With their Eurocentric ideology overriding facts, the Carnegie Council reported: “President Roh has successfully led the country through these changes [Korean democracy].” Gaston Sigur, President Reagan’s special envoy to Korea in 1987, contributed an article to the report in which he affirmed that, “Roh led Korea toward a full-blown democracy”; Roh “curbed the power of the police”; his policies “included the freeing of labor.”8 Such experts completely conflate fact an ideology because of their understanding of civil society. The Carnegie Council report included statements like, Korean values are “incompatible with democracy” and Korean people are “uncomfortable with democracy” and want “to be ruled by an elite.”

Whatever their differences, U.S. liberals like the Carnegie Council, conservatives like Samuel Huntington, and critical thinkers like Cumings share an underestimation of the significance of Korean civil society. This diminution of Korean civil society and the blaming of Korean character, present in even some progressive accounts of Korea, follow in the footsteps of a century of subordination of Korea to U.S. and Japanese interests.

For Bruce Cumings, Korean civil society was asleep and “began to waken again with the February 1985 National Assembly elections.” Like Gregory Henderson, Cumings believes traditional Korea did not enjoy a strong civil society: “in the Republic of Korea strong civil society emerged for the first time in the 1980s and 1990s, as a product and also a gift of the extraordinary turmoil of Korea’s modern history.” Cumings’ understanding of civil society mistakes European images of it for its universal appearance, specifically in the notion of the autonomous individual and Western forms of civil society. Cumings invokes Habermas’s ideal speech community, believing “intellectuals are the primary carriers of a self-conscious civil society,” but he somehow fails to consider Korean intellectuals in Gwangju during the 1980 uprising or traditional Korean intellectuals in private academies. For him, like Habermas, a Eurocentric frame leads to hypostasizing the Western individual and developing universal categories based upon the assumption that the historical trajectory of Europe defines that of every society.

Cumings believes that civil society exists between the state and the mass of people, not in the actual relationships among people in their daily lives. He also ascribes too much power to government: Park Chung-hee’s coup was an act of “shutting down civil society” and “civil society began to waken again with the February 1985 National Assembly elections.” Like many Western democratization theorists, he believes Japan became a democracy after 1945 and South Korea after 1993. The paths of these two countries to parliamentary democracy were quite different. Great struggles emanating from civil society won democratic reform in Korea—unlike in Japan where the electoral system was mandated by the US from above. Nevertheless, Cumings believes “the ROK still falls short of either the Japanese or American models of democracy and civil society” because of the continuing existence of the National Security Law (NSL)—the 1948 measure derived from a Japanese model under heavy pressure from the United States.9 Without any doubt, the continuing division of Korea distorts many aspects of its political and economic life. Yet the NSL is an instrument of state power and has little to do with the strength of civil society. Rather than understanding civil society as something that can be shut down by a dictator or reawakened in elections, civil society is a vast web of relationships in ordinary people’s everyday lives, not a dependent variable of government or marketplace.

Emphasizing the role of civil society might also help to de-mythologize multinational Korean corporations, whose reputations have been enhanced by international knowledge of the May 18 uprising. Clearly Korean people's actions in fighting for and winning democracy are an inspiration not only to Asians but also to Africans, Latin Americans, and also Europeans and North Americans. Propagation of the news of the qualm to uprising therefore helps to build a mystique about Korean People's love of freedom. At the same time, however, Korean corporations seeking to maximize profits in their overseas ventures often have terrible reputations for maltreatment of workers through authoritarian and sexist practices, underpayment or nonpayment of wages, and even use of violence or the threat of violence against employees. Delinking Korean corporate interests from 518 is an important task.

Section Notes:

6 Kim Yong-cheol, “The Kwangju Uprising and Demilitarization of Korean Politics,” in 5– 18관련 논문과 작품 영역 및 저술 사업: 2001. 5–18 20주년 기념 학술연구사업 연구 소위

(Gwangju: 전남대학교 5–18 연구소: 2001).

7 See Jung-kwan Cho, “The Kwangju Uprising as a Vehicle of Democratization,” in Contentious Kwangju: The May 18 Uprising in Korea’s Past and Present, ed. Gi-Wook Shin and Kyung Moon Hwang (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003), 76–77.

8 Gaston Sigur, “A Historical Perspective on U.S.-Korea Relations and the Development of Democracy in Korea 1987–1992,” in Democracy in Korea: The Roh Tae Woo Years, ed. Carnegie Council (New York: Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs, 1992), 9–17.

9 For Cumings statements, see Cumings, “Civil Society,” in Civil Society in West and East,” in Korean Society: Civil Society, Democracy, and the State, ed. Charles Armstrong (London: Routledge, 2007) 9, 17, 22-24, 26.

3. Empirically to challenge and refute the myths currently circulating of North Korean influence on the uprising

Although it is a very important contemporary issue for 518 in Korea, I will not go into much detail about very ridiculous statements currently circulating here about the North Korean influence on the events of 1980. Almost all English-language accounts of the uprising understand clearly that North Korea's influence was minimal or nonexistent. At the time the American Embassy's internal documents made quite clear that North Korea was not involved. The Embassy voiced concern, however, that media censorship by the Chun Doo- hwan dictatorship caused more South Koreans than ever to listen to the North’s radio reports about events in Gwangju. Beginning about ten years ago, right-wing web sites began propagating false stories about 518. Last year, after publication of Kim Dae Ryung’s book claims no citizens were killed in Gwangju by the ROK army and that the uprising was remotely controlled by North Korea, right-wing forces have accelerated their campaign of distortions. The book cunningly distorts history. It is vital that its fabrication of “facts” be empirically challenged.

Even a glance at 26 years of research about 518 leaves little doubt of the enormous influence of the Gwangju People’s Uprising all over the world. The 518 Memorial Foundation, the May 18 Research Institute at Chonnam National University, and a handful of other organizations have been instrumental in spreading news of the uprising, or “globalizing 518.”

English-Language Bibliography

Charles Armstrong (editor), Korean Society: Civil Society, Democracy and the State (London: Routledge, 2002)

Juna Byun and Linda Lewis (editors), The 1980 Gwangju Uprising After 20 years: The Unhealed Wounds of the Victims (Seoul: Dahae Publishers, 2000)

Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: Norton, 1997) George Katsiaficas, Asia’s Unknown Uprisings Vol. 1: South Korean Social Movements in the 20th Century (Oakland: PM Press, 2012).

Martin Hart-Landsberg, The Rush to Development: Economic Change and Political Struggle in South Korea (New York” Monthly Review Press, 1993)

Martin Hart-Landsberg, Korea: Division, Reunification, and US Foreign Policy (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1998)

Kyun Moon Hwang and Gi-Wook Shin, (editors) Contentious Kwangju: The May 18th Uprising in Korea's Past and Present (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003)

Hagen Koo, Korean Workers: The Culture and Politics of Class Formation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001)

Namhee Lee, The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007)

Linda Lewis, Laying Claim to the Memory of May: A Look Back at the 1980 Kwangju Uprising (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002)

Kenneth Wells (editor), South Korea’s Minjung Movement: The Culture and Politics of Dissidence (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1995)